By: Meryl Carlton

This year is different. Instead of waiting in line for hours before the game starts to get a spot in the front row of the student section on gameday, I am pulling into the West lot of the stadium that only has about 10 other cars at the moment. The RMC volunteer asks to see my mobile ticket that is reserved for guests of the players and coaches. I have one, as I am lucky enough to know someone on the team. I park where I am directed, at least a spot away on both sides from any other car. It is a spot someone would have paid a lot of money for a year ago. We are told we cannot loiter outside the stadium. Once you exit your car, there are cops on segways to usher you inside the gates.

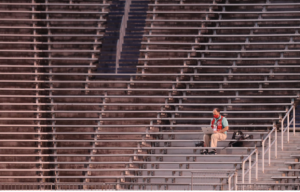

There is no line for security. Entering through metal detectors with your clear bag checked, you proceed to the kiosk where you scan your mobile ticket. You do not pass many people entering, because no one is allowed to stand around. There are two concession stands open, with two or three workers at each, and their selection is limited. You can still get popcorn and Bojangles’ chicken tenders, but there is nobody behind the counter frying up burgers and hot dogs like usual. When you pass through the section entrance and the field comes into view, the stands around you are empty. There are cushioned stadium seats in groups of twos or fives spread out in the bleachers and you find one to sit in, socially distant from everyone else. If you are sitting on an actual bleacher, a stadium employee will ask you to move. If your mask is not covering your mouth and nose, a stadium employee will ask you to put it all the way on. Most people have had their masks customized for UVA, and a lot of players’ families have put their names and jersey numbers on them. You are allowed to remove them if you are eating or drinking.

“This is just really sad,” one parent says as they enter into the stadium for the first time since the COVID-19 restrictions have been set in place.

You can hear the players interacting with each other, the other spectators’ conversations, and the coaches yelling at the players after a bad play. When you are cheering, everyone around you can hear exactly what you are saying, which might cause you to be more cognizant of what comes out of your mouth, or deter you from cheering at all. When the stadium is filled with tens of thousands of people, you do not have that self-consciousness. This is what it is like to attend a football game at Scott Stadium in 2020.

On July 29, the Atlantic Coast Conference announced their 2020 plan for the football season, over four months after UVA President Jim Ryan sent an email announcing the University would be moving online until further notice. After months of uncertainty, while school stayed online and sports were on an indefinite hiatus, the ACC announced that all seven fall sports, including football, would play their seasons, beginning in September. But as those seasons began, they were far from ‘normal’.

Due to health and safety considerations, UVA Athletics limited stadium occupancy to 1,000 people, only allowing families of players and coaches to attend. While many hoped Scott Stadium would open to more spectators over time, they watched other ACC schools like Clemson admit just under 20,000 fans, while UVA held firm at 1,000. Without the fourth side– a term the team came up with for the band, cheerleaders, dance team, student section, and all of the fans–the games felt lackluster, quiet, and strange.

On game days the energy inside Scott was dreary in comparison to all the years before, with an audio recording of cheers coming from the scoreboard’s speakers and the less than 1,000 people in the stadium trying, but failing, to fill it with noise.

In years prior, Scott Stadium was a rowdy, raucous Saturday afternoon gathering. The marching band performed before games, making shapes with their bodies that left the audience perplexed at their ability to play an instrument and move into formations at the same time. The grassy hill was packed with students who would slide through the mud when it was raining and rush onto the field after big wins. Fans would travel from as far as Hawaii and South Africa to cheer on the Cavaliers, packing the stadium with tens of thousands of voices.

Students and fans alike were devastated they were forced to cheer the Cavaliers on through a television screen only. It was particularly hard for fourth year students who would not get the opportunity to huddle up with their friends one last time in the student section to keep warm during those winter games, when the sun had gone down and the temperature dropped. They would not be able to stand in line again for free pizza and T-shirts before kickoff. Some experiences are hard to replicate, and home football games for college seniors is one.

Along with students, the fans were also upset they could not cheer on their team. 11-year-old Jackson Maschal (pictured on the right) is an avid UVA Sports fan. He anticipates football season: live games, family time, cheering for the Hoos. He loves the energy on grounds on game day, and he hopes to one day attend UVA and play for the basketball team.

“I miss the feeling of being there with all of the excitement… you just don’t get that watching it on TV,” Maschal said.

For kids like Maschal, the inability to attend games means missing important experiences like cheering amidst the thousands of fans on a fall Saturday in Charlottesville. At games, Maschal gets to watch his favorite players, like Wayne Taulapapa, live and in action on the field. That kind of excitement cannot be mimicked anywhere else, and that excitement through the eyes of a child is limited by time.

Without the students and fans there to help energize the team, it seemed as if the sadness of the COVID-19 situation was starting to affect how the team was playing. After winning their home season-opener against Duke, the Cavaliers lost the next four consecutive games.

“We miss the support [of fans] and so we’re really focusing on the fourth side, which is our own players, because we know there’s another fourth side supporting from afar, but we’re really trying to help that become our advantage as well,” UVA Head Coach Bronco Mendenhall said.

Mendenhall also commented on the atmosphere in Scott Stadium when the team returned to home after an upsetting defeat to Clemson in Death Valley, saying, “When I walked in, it was like whoa. Wow, this doesn’t feel like, I can’t say it doesn’t feel like home, but it doesn’t feel like Scott stadium normally does–There’s this energy and there’s this chemistry that almost overtakes you,” Mendenhall said.

With no plans to start introducing fans back into Scott Stadium, the team had to look to themselves to create the energy once filled by 61,000 people. Staring at a 1-4 record, the Cavaliers realized they were the difference-makers here, and that their attitude had a heavy affect on their performance.

While the team had to make sudden adjustments to such radical changes this season, the players and coaches do not believe the lack of fans was what had a major impact on the team’s performance. Several players even saw a silver lining with a quieter stadium. Junior running back Wayne Taulapapa said in a press conference how the lack of fans allowed the team to more easily hear play calls and cadences.

“Football is football at the end of the day,” Taulapapa said. “What excites me more is my brothers on the sidelines. That fourth side is super important to us when we are on the field, but I wouldn’t say it’s much of a difference.”

Even though the crowd helps build momentum at the games, it is also important that the players create that energy for themselves. Mendenhall has bragged about the competitive spirit and resilience of his team this season, and how their beliefs in themselves and their abilities is something that inspires him in the wake of such a strange season.

In October, coming off of their fourth consecutive loss, the team re-entered Scott Stadium for their third home game that season, but this time they were used to the less noisy atmosphere and were ready to create their own energy as they faced the UNC Tarheels.

This game felt different. There were still the usual 1,000 family members and friends in the stands, but the energy was stronger than it had been the first two home games. When the players entered the stadium, it was clear that something had changed within them. They were feeding off of each other on the sideline, dancing and hyping each other up. The crowd had also seemed to have made some adjustments from previous games, letting their guards down to cheer on their team no matter the fact that people could hear them clearly. It was as if all of the superficial things that people thought were important to football were gone, and now the team was just playing the game out of the pure enjoyment of it.

With less than three minutes left in the final quarter of the game, the Cavaliers were clinging to a 44-41 lead. On the second down, UVA quarterback Brennan Armstrong was running through a hole when one of UNC’s defensive linemen fell on the outside of his knee with his entire bodyweight. The stadium fell completely silent. The fake cheering through the audio system ceased. Everyone watched nervously as the quarterback, who had just returned from concussion protocol suffered the weekend before, was lying on the field, motionless.

From the fifth row of the stadium, a fan could hear one of the medics on the field yell, “He’s fine”, before trainers stood him up and helped Armstrong limp off the field. The audience clapped for him, but the energy in the stadium had diminished.

Virginia’s Keytaon Thompson, who earlier had rushed for a one-yard touchdown, replaced Armstrong at quarterback on the third down. The Cavaliers were unable to get the first down on the next play. The clock was ticking; Mendenhall had to decide what play to call, as the Cavaliers were fourth-and-three from the 42-yard line. UVA kicker Nash Griffin walked onto the field as the few UVA fans in the stands bickered about whether or not the ball should be punted.

“He has to punt it” one fan yelled to his son, “We can’t give them the ball on the 42-yard line”.

“No, we have to go for it here, I think we should fake the punt,” the son responded.

The ball was snapped to Thompson, who ran to the left when the play was designed for him to go right. He broke through a pair of tackles, diving for the first down. The stadium erupted into cheers, and the boy looked at his dad. “I told you they were going to fake the punt,” the son said. The dad laughed in disbelief. After a hand-off and two knees taken by backup quarterback Lindell Stone, the clock had run down and the game was over. The Cavaliers had broken their four-game losing streak on their home field.

The team had proven to themselves that at the end of the day, the most important thing about football is the love of the game and the strength of their own relationship. When they changed their attitude towards the differences the pandemic brought their season, they were able to finally make a breakthrough. While the Cavaliers had to adjust to limited fans, new protocol, and a new head quarterback this season, they have possibly found something within themselves that they would not have found otherwise. The familial aspect of the team is something important to Mendenhall’s football program and it has clearly been strengthened this season. To the Cavaliers, this football family comes first, last, and always.