On January 2nd, 2016, UVa Third Year Otto Warmbier was detained in Pyongyang, North Korea and convicted for subversion. One year later, Warmbier remains incarcerated and little progress has been made in securing his release.

After celebrating New Year’s 2016 in North Korea, Warmbier was detained by armed guards in the Pyongyang airport just minutes before boarding a flight back to the U.S. The Cincinnati, Ohio native had spent five days on an organized tour led by the Chinese agency Young Pioneers Tours. While the charges he faced were initially unclear, North Korea’s Central News Agency announced in a January 20th press conference that an American tourist was in custody for committing “hostile acts against the DPRK.” Officials alleged that Warmbier was colluding with the FBI, a Unitarian church in his hometown, and UVa’s Z Society to spy on the communist regime.

The state-run media outlet slowly released additional information on Warmbier’s charges over the following weeks. It was revealed that he was accused of stealing a political propaganda banner from a restricted area in the Yanggakdo International Hotel in the nation’s capital, where he was staying along with over 100 westerners–including other Americans.

In a February 29th press conference, Warmbier admitted to the crime in a two-minute, scripted statement. North Korean officials claim that the conference was held “at [Warmbier’s] own request,” but the confession was evidently made under duress. In the footage of his statement released online, Wambier was visibly distraught as he begged for forgiveness and bowed deeply in apology.

“I never, never should have allowed myself to be lured by the United States administration to commit a crime in this country,” Warmbier said. “I wish that the United States administration never manipulate people like myself in the future to commit crimes against foreign countries. I entirely beg you, the people and government of the DPRK, for your forgiveness. Please! I made the worst mistake of my life.”

His confession led to an expedited criminal hearing, although the legal proceedings were far from transparent. In early March, the Central News Agency released a video that allegedly showed Warmbier committing the crime. However, the perpetrator’s face remained concealed, making identification impossible. Nonetheless, the video served as the primary piece of evidence in the one-hour, public trial that Warmbier was given on March 15th. The North Korean Supreme Court found him guilty of subversion and sentenced him to 15 years’ hard labor, which he now serves.

In the year since his arrest, little progress has been made toward freeing Warmbier. While the State Department and the U.S. Embassy in Seoul, South Korea have been working to secure his release, Warmbier’s situation has not meaningfully improved. Efforts to free Otto are complicated by the United States’ lack of diplomatic relations with North Korea. The hostile nation’s leader, Kim Jong Un, has made countless threats toward the U.S. and routinely violates UN sanctions on its burgeoning nuclear program. America consequently counts on the Swedish Embassy in Pyongyang to negotiate with the DPRK on behalf of its interests.

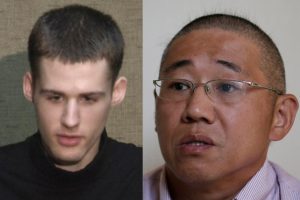

These stringent sanctions, however, give American diplomats reason to believe that Warmbier will not serve the entirety of his 15-year sentence. North Korea historically has used Western prisoners–and Americans in particular–as bargaining chips to alleviate sanctions or pursue other political interests internationally. In the Fall of 2014, Obama engendered Kim Jong Un to order the release of American detainees Kenneth Bae and Matthew Todd Miller. Bae served only 735 days of his 15-year sentence, while Miller served 212 days of a 6-year sentence.

Bae has since offered much insight into his experience as the DPRK’s longest-held American prisoner since the Korean War.

“I worked from 8 a.m. to 6 pm. at night, working on the field, carrying rock, shoveling coal,” Bae told CNN in a 2016 interview.

In addition to physical pain, Bae reported that prisoners endured verbal abuse form North Korean officials that intended to break their spirit and instill the belief that their country had abandoned them. He said that one prosecutor repeatedly told him, “‘No one remembers you. You have been forgotten by people, your government. You’re not going home anytime soon. You’ll be here for 15 years. You’ll be 60 before you go home.'” Bae has since published a memoir, “Not Forgotten: The True Story of My Imprisonment in North Korea,” that tells his story.

Miller reported a similar experience to an Associated Press reporter, saying that prison life featured eight hours of outdoor physical labor per day. While he remained in relatively good health, Miller said that he was not allowed contact with anyone, creating a disheartening sense of isolation.

While the ex-prisoners’ stories offer hope that Warmbier will one day return home safely, the unpredictable nature of Kim Jong Un’s regime make the timing and circumstances of his release impossible to forecast. Kim Jong Un, like his father Kim Jong Il before him, has typically agreed to release prisoners after the U.S. pledges aid or has its dignitaries extend political gestures toward the aggressive nation. Visits from powerful American officials have also catalyzed prisoners’ releases in the past; in 2009, former president Bill Clinton traveled to North Korea in a successfully attempt to free two American journalists, Euna Lee and Laura Ling, who had been detained for five months after accidentally crossing the border from China. Such diplomatic measures offer the rogue regime the legitimacy it longs for on the international stage. However, Kim Jong Un proves to be an even more insecure and unpredictable negotiating partner than his father, making him less willing to accept pomp and circumstance as reason for exoneration.

Regardless of the mounting diplomatic obstacles, critics blame the Obama administration for not doing enough to bring Otto home. Warmbier is one of three Westerners–two American and one Canadian–currently known to be detained in North Korea, all on suspicion of espionage. While a Obama was able to secure Miller and Bae’s releases in 2014 with diplomatic goodwill and a hand-delivered letter, no comparable measures have been taken in the nine months since Warmbier’s imprisonment.

While the impending transition to Trump’s presidency on January 20th has many Americans concerned, proponents of Warmbier’s immediate release hope that the 45th president will take the hard stance on North Korea necessary to bring the prisoners home. Despite uncertainty about the future of US-Korean relations, many hope that the internationally-observed transfer of power will change the tone of negotiations and lead to Warmbier’s release.

Agen Mata-mata amerika dan sekutu